Among all pancreatic tumors, solid pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas (SPT) is rare and has low malignant potential, accounting for approximately 0.9%–2.7% of pancreatic tumors in adults (1). As described by Frantz in 1959, SPT mainly occurs in young women (mean age 28 years) and its frequency has recently increased (2). SPT is usually recognized as a large mass with a cystic component predominantly located in the tail of the pancreas (3, 4). Patients with SPTs typically have presented nonspecific symptoms such as abdominal discomfort, nausea, vomiting, weakness, or pain (5). The recommended therapy for SPTs is surgical resection through open or laparoscopic resection, depending on tumor location and/or size (6, 7). The overall survival following surgery is generally favorable with low recurrence for patients with SPTs (8). However, SPTs outside the pancreas are exceedingly rare and this is the first case to report a histologically documented case of a male patient with extrapancreatic SPT with superior mesenteric artery (SMA) invasion. Given the unusual combination of extrapancreatic location, male gender and solid nature without a cystic component, it is instructive to document this case to highlight the diagnosis and treatment of SPTs.

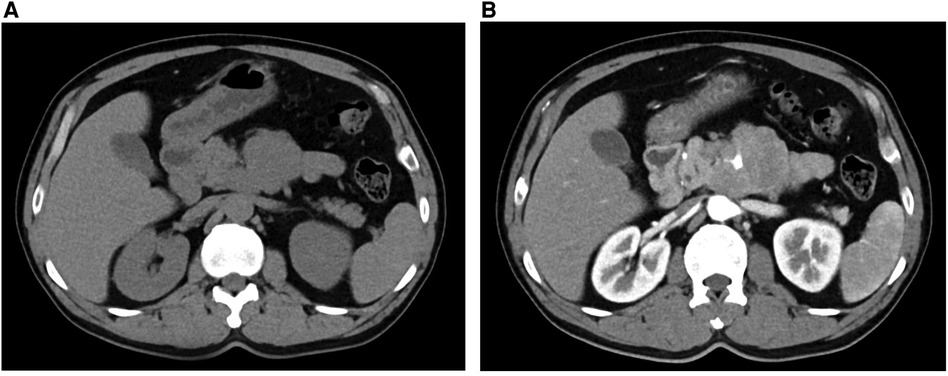

2 Case presentationA 47-year-old man with cerebral infarction 1 year prior with a 2-day history of intermittent abdominal pain, associated with anorexia. A thoracic CT scan revealed an occupying lesion below the neck of the pancreas (Figure 1A), which on contrast-enhanced CT was seen to be a 7.7 × 6.0 cm lesion in the vicinity of the left aspect of the pancreatic uncinate process, encasing the SMA and some of its branches (Figure 1B). This raised suspicion for a pancreatic uncinate of retroperitoneal to neoplasm. The radiology department advised that the lesion be biopsied. Blood parameters, including CEA, CA-199, AFP and PSA were normal (Table 1), which were consistent with previous cases of SPTs even with metastases (9), though IL-6 was raised at 9.06 pg/L in this case. A primary diagnosis of a pancreatic space-occupying lesion was made at the very beginning of the study due to the CT findings, despite the presence of normal tumor markers. Following detailed discussion between the physicians and patient, a laparoscopic retroperitoneal tumor biopsy was suggested to determine whether the lesion was malignant or benign because the SMA was surrounded by this lesion, limiting the opportunity for complete resection of the tumor.

Figure 1. CT (A) and contrast-enhanced CT (B) showing an occupying lesion below the neck of the pancreas.

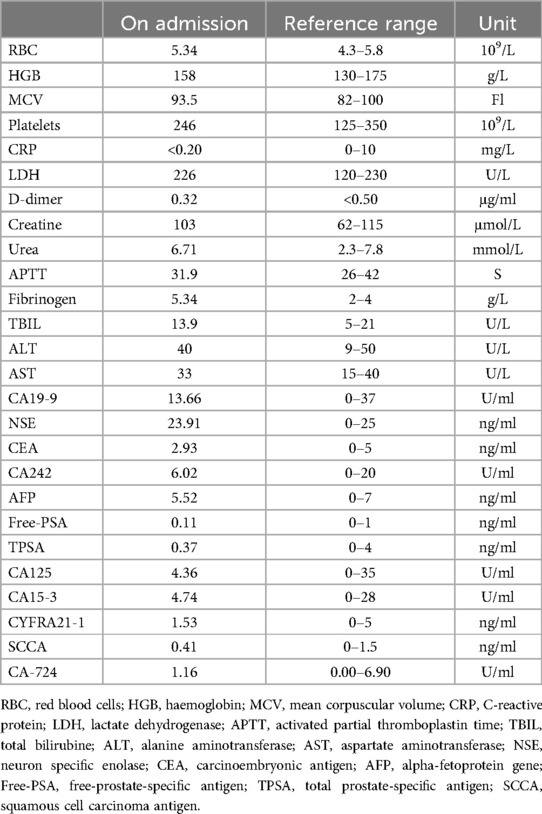

Table 1. Patient's laboratory results.

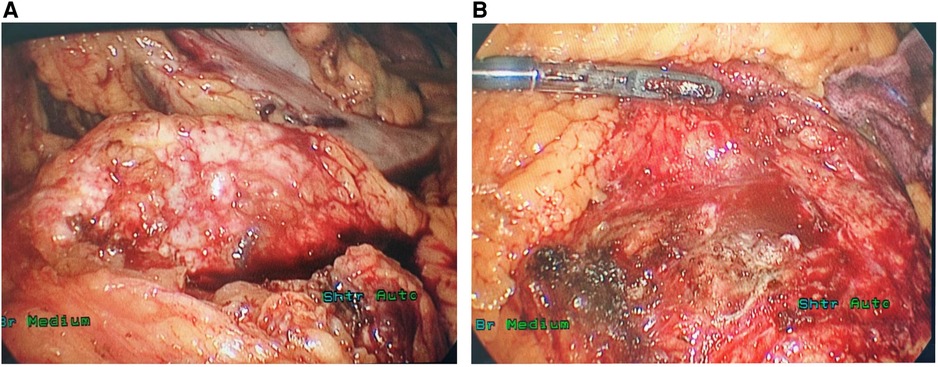

During the surgery, ascites was not found in the abdominal cavity. No abnormal nodules were observed on the surface of the liver, abdominal wall, pelvis, greater omentum, intestinal walls or mesentery, suggesting no metastasis. After opening the gastrocolic ligament, no obvious space-occupying lesion was observed on the surface of the pancreas. Via the approach of the inferior colon, a large, solid, firm, fixed and highly vascularized tumor was observed behind the root of the mesentery, completely encasing the mesentery (Figures 2A,B). After opening the retroperitoneum, the tumor was carefully biopsied to avoid damage to the SMA. The tumor specimen was then sent for rapid pathological examination, which considered neuroendocrine tumor.

Figure 2. The ectopic SPT surrounded the SMA outside the pancreas (A) and no lesion was identified in the pancreas during the operation (B).

The standard histopathological report revealed that the neoplasm corresponded to the SPT. The tumor specimen measured approximately about 0.8 × 0.6 × 0.3 cm grossly and subsequent histopathology revealed cercariform cells with pseudopapillary formations (Figures 3A,B). The tumor cells expressed PR(+),β-Catenin(+), LEF1(+), CD10(+), CD56(+), P53(+, 5%), Syn(+), ATRX(+), DAXX(+), MGMT(+), Rb(+), CgA(−), SSTR2(0), CK(−), INSM1(−), CD20(−), CD79a(−) and Ki-67 positive rate 5%.

Figure 3. Histological examination showing characteristics of SPT: papillary structures (A) and cercariform cells (B): slight nuclear atypia (triangles) and delicate elongation of the cytoplasm (arrows). (hematoxylin-eosin, original magnifications ×200[a], ×400[b]).

During the follow-up of 3 months after surgery, the patient experienced a favorable recovery revealing no signs of further progression. This patient only takes Creon regularly, with a satisfactory management of blood glucose levels.

3 DiscussionSPT is regarded as a rare tumor, accounting for approximately 0.9%−2.7% of pancreatic tumors. Grossly, SPT is characterized by an encapsulated mass with internal hemorrhage, cystic degeneration and calcification (10). Various names have been used to describe this rare neoplasm such as Frantz tumor and solid and papillary epithelial neoplasm. Moreover, the tumor has a predilection for females in a ratio of 10:1. Fewer than 30 cases of extrapancreatic SPTs have been described. Most of the ectopic SPTs are located in the mesocolon (11), while others have been reported in ovary (12), and testis (13). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of ectopic SPT that was located in the retroperitoneum which at the same time showed SMA invasion.

In this case, a male patient diagnosed with extrapancreatic SPT was reported (10). Radiological investigations demonstrated a 7.7 × 6.0 cm tumor, encasing the SMA and its branches. Pathological examination further confirmed the diagnosis of ectopic SPT. We conclude that to diagnose ectopic SPT, histopathological examination is regarded as the gold standard, although most SPTs are indicated by hypodense cystic lesions on CT and normal tumor markers. To be specific, contrast-enhanced CT usually reveals an encapsulated large mass with a thick wall or cystic components inside (11).

Currently, laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy is a widely used approach for SPT resection, particularly for young women. Other therapies, such as gemcitabine treatment, radiotherapy and hormonal therapy are also used for unresectable SPTs, with no consensus on their treating values temporally (14, 15). Due to the rarity of reported ectopic SPTs, although complete surgical excision is curative in SPT patients limited to the pancreas, more detailed guidelines for ectopic SPTs are still lacking. For this patient, the SPT was derived from the retroperitoneum encapsulating the root of the SMA, indicating difficulty in subsequent resection. Thus, the laparoscopic retroperitoneal tumor biopsy approach can be a better alternative. In addition, the treatment decision before surgery is quite difficult due to the complexity of the pancreatic tumor. The primary treatment of cytoreduetive surgery combined with chemotherapy and immunotherapy may be considered if the lesion is aggressive. Considering the promising long-term prognosis of SPT patients, even those with metastasis, for whom a 10-year disease-specific survival rate of 96% has been reported (15), additional treatments for this patient may include chemotherapy, hormone therapy, radiofrequency ablation and cryoablation, although the benefit of these treatments is poorly understood. Furthermore, regular clinical ultrasonographic investigations of this patient are also recommended for monitoring this tumor progression. We still recommend a two-stage cytoreductive surgery of SPT for this patient if he is agreeable to it.

Based on our adequate experience of laparoscopic techniques, we successfully biopsied this tumor which at pathology work-up was shown to be an SPT. A high Ki-67 positive rate may predict the malignant potential and poor prognosis of SPT (2), and we expect this patient with a 5% Ki-67 positive rate to have a long survival.

4 ConclusionSPT is a rare tumor that occurs mainly in young women. Exploratory laparotomy/laparoscopy with biopsy and frozen section is recommended for such tumors in order to inform next steps.

Data availability statementThe original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statementWritten informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributionsAZ: Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft. KW: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. XT: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. SC: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. JX: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. HL: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. LW: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. FL: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

FundingThe author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

This research was funded by the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province, China (ZR2020MH231).

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's noteAll claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

AbbreviationsSPT, solid pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas; SMA, superior mesenteric artery.

References1. La Rosa S, Bongiovanni M. Pancreatic solid pseudopapillary neoplasm: key pathologic and genetic features. Arch Pathol Lab Med. (2020) 144:829–37. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2019-0473-RA

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

2. Liu M, Liu J, Hu Q, Xu W, Liu W, Zhang Z, et al. Management of solid pseudopapillary neoplasms of pancreas: a single center experience of 243 consecutive patients. Pancreatology. (2019) 19:681–5. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2019.07.001

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

3. Klöppel G, Kosmahl M. Cystic lesions and neoplasms of the pancreas. Pancreatology. (2001) 1:648–55. doi: 10.1159/000055876

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

6. Zhang H, Wang W, Yu S, Xiao Y, Chen J. The prognosis and clinical characteristics of advanced (malignant) solid pseudopapillary neoplasm of the pancreas. Tumour Biol. (2016) 37:5347–53. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-4371-5

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

7. Mazzarella G, Muttillo EM, Coletta D, Picardi B, Rossi S, Rossi Del Monte S, et al. Solid pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas: a systematic review of clinical, surgical and oncological characteristics of 1384 patients underwent pancreatic surgery. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int (2024) 23:331–8. doi: 10.1016/j.hbpd.2023.05.004

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

8. Wang W-B, Zhang T-P, Sun M-Q, Peng Z, Chen G, Zhao Y-P. Solid pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas with liver metastasis: clinical features and management. Eur J Surg Oncol. (2014) 40:1572–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2014.05.012

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

9. Ma Y-Y, Chen J-B, Shi J-J, Niu L-Z, Xu K-C. Cryoablation for liver metastasis from solid pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas: a case report. World J Clin Cases. (2020) 8:398–403. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i2.398

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

10. Papavramidis T, Papavramidis S. Solid pseudopapillary tumors of the pancreas: review of 718 patients reported in English literature. J Am Coll Surg. (2005) 200:965–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2005.02.011

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

11. Tornóczky T, Kálmán E, Jáksó P, Méhes G, Pajor L, Kajtár GG, et al. Solid and papillary epithelial neoplasm arising in heterotopic pancreatic tissue of the mesocolon. J Clin Pathol. (2001) 54:241–5. doi: 10.1136/jcp.54.3.241

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

12. Deshpande V, Oliva E, Young RH. Solid pseudopapillary neoplasm of the ovary: a report of 3 primary ovarian tumors resembling those of the pancreas. Am J Surg Pathol. (2010) 34:1514–20. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181f133e9

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

13. Michalova K, Michal M, Sedivcova M, Kazakov DV, Bacchi C, Antic T, et al. Solid pseudopapillary neoplasm (SPN) of the testis: comprehensive mutational analysis of 6 testicular and 8 pancreatic SPNs. Ann Diagn Pathol. (2018) 35:42–7. doi: 10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2018.04.003

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

14. Maffuz A, de Thé Bustamante F, Silva JA, Torres-Vargas S. Preoperative gemcitabine for unresectable, solid pseudopapillary tumour of the pancreas. Lancet Oncol (2005) 6:185–6. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(05)01770-5

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

15. Rebhandl W, Felberbauer FX, Puig S, Paya K, Hochschorner S, Barlan M, et al. Solid-pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas (Frantz tumor) in children: report of four cases and review of the literature. J Surg Oncol. (2001) 76:289–96. doi: 10.1002/jso.1048

Comments (0)