Caring for ill cancer patients imposes a considerable burden on families, significantly reducing quality of life (QoL).[1-3] Based on the close linkage of family QoL with caregiving activities and patient QoL,[4,5] the importance of QoL, not only for patients but also for their families, has been highlighted as a goal of palliative care in clinical guidelines.[6] The QoL of family caregivers (FCs) varies according to the disease trajectory;[7] However, overall, palliative care rather than curative settings affects QoL more.[8] In hospice settings, several factors have been identified as associated with FC QoL, such as caregiving burden, economic burden and caregiver mental health.[8,9]

Preparedness for death is defined as caregivers’ perception of their readiness for a patient’s death.[10] It involves how accurately a caregiver knows the patient’s prognosis and how he/she prepares emotionally for the patient’s death. Preparedness can be assessed in terms of emotional and practical aspects,[11] which indicates that readiness for a patient’s death consists of emotions related to the death itself and challenges in daily living, such as new household responsibilities and funeral arrangements. The preparation stage has been reportedly associated with caregivers’ coping strategies, perception of financial adequacy, bereavement response and mental health, such as depression and anxiety.[10] Thus, a lack of preparedness for death can be linked to poor FC QoL, as unprepared FCs might experience a higher care burden and more emotional distress than well-prepared FCs. Although several studies have reported associations between FC preparedness and caregiving outcomes, such as bereavement response or emotional distress, studies regarding the association of preparedness with caregivers’ QoL are relatively scarce.[12] In a Swedish study of widowers, a low degree of preparedness increased the risk of low or moderate QoL 4–5 years after the loss (relative risk, 1.18; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.3– 2.6).[13] However, to our knowledge, no study has examined preparedness for death and QoL amongst FCs of patients with cancer in Korea. As end-of-life care should be considered under diverse sociocultural circumstances,[14] tailored research on different cultures or countries is needed. Therefore, we aimed to assess the preparedness state of FCs of patients with terminal cancer and examine the association between FC preparedness and their QoL.

MATERIALS AND METHODS Study design and participantsThis study was based on a multicentre cross-sectional survey conducted in nine inpatient palliative care units in South Korea. We collected data from June 2021 to May 2023, mostly within 1 week of admission. FCs were eligible to participate if they were responsible for most patient care, were older than 20 years and were able to provide information regarding the survey. We consecutively administered questionnaires to eligible FCs. The researchers explained the aim and scope of the survey to the FCs and administered self-report questionnaires after obtaining their consent. To minimise missing values, the researchers checked the responses immediately after receiving the completed surveys and inquired about any missing data. A total of 170 FCs were included in the statistical analyses.

Measures QoLThe Korean version of the Caregiver QoL Index-Cancer (CQOLC-K) was used to assess FCs’ QoL. The reliability/validity of CQOLC-K was documented in a previous study.[15] It consists of 35 items, each rated on a five-point scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 4 (very much). Ten items pertain to burden, seven to disruptiveness, seven to positive adaptation, three to financial concerns and eight to additional factors (sleep disruption, satisfaction with sexual functioning, day-to-day focus, mental strain, information about the illness, patient protection, management of patient’s pain and family interest in caregiving). A total score was obtained by adding all item scores, and domain scores were calculated by adding the item scores for each domain. The maximal total score was 140, with higher scores indicating better QoL.[15] We categorised the participants into low- and high-QoL groups according to the mean value (70) of the total CQOLC-K score.

Preparedness for deathThe FCs’ perceptions of their readiness for patient death were assessed in terms of both emotional and practical aspects. Emotional preparedness was evaluated based on responses to the question, ‘I am emotionally well-prepared for the patient’s death’. Practical preparedness was evaluated based on responses to the question, ‘I am practically well-prepared for the patient’s death such as new responsibilities, future plans and funeral arrangements’. Responses were ranked on a five-point scale as follows: (1) Not at all, (2) no, (3) average, (4) yes and (5) very much so.[10] We categorised participants into low and high-preparedness groups according to the median value of each preparedness score.

CovariatesWith reference to our prior study on a similar issue,[16] demographic information, such as age, sex, relationship with the patient, education level, marital status and religion, was obtained. Relationships with patients were categorised as ‘spouse’ or ‘others’ (including children, siblings, parents and others). Education level was categorised as ‘high school or lower’ or ‘college or higher’. Marital status was categorised as ‘married’ or ‘unmarried’ (including never married, divorced, separated or widowed). Religious affiliation was categorised as ‘no religion’ or ‘religion’ (including Protestantism, Catholicism, Buddhism and others). FCs’ resilience was assessed using the Connor– Davidson Resilience Scale, which comprises 25 items on a five-point scale from 0 (not at all confident) to 4 (completely confident). Higher scores indicated greater resilience.[17]

Objective burden of care, social support and family functioning levels were assessed to evaluate the caregiving environment. The burden of care was evaluated as caregiving hours per day, days per week and months per year. As an evaluation tool for social support level, the Medical Outcome Study Social Support Survey was used, which comprises 19 items rated on a five-point scale, from 1 (not at all) to 5 (all of the time). Higher scores indicate greater social support.[18] The family function was assessed using the Korean version of the family Adaptation, Partnership, Growth, Affection and Resolve (APGAR). The family APGAR comprises five items rated on a three-point scale ranging from 0 (hardly ever) to 2 (almost always). The total score ranged from 0 to 10, with higher scores indicating greater satisfaction with family functioning.[19]

Statistical analysisThe characteristics of participants according to the total QoL score of FCs were compared using the Chi-square test for categorical variables and the t-test for continuous variables. Logistic regression analyses were performed to identify factors associated with high QoL, and linear regression models were used to estimate QOL scores in total and in four subdomains (burdensomeness, disruptiveness, positive adaptation and financial concerns) according to preparedness level. Regression coefficients for total QoL scores were calculated for the educational level, resilience, social support and family function subgroups. All statistical analyses were performed using STATA/MP version 17.0 (StataCorp., College Station, TX, USA), and a statistically significant P-value was defined as <0.05.

RESULTS Characteristics of study participantsTable 1 shows the characteristics of the study participants according to FCs’ QoL. Low and high QoL scores were determined using mean CQOLC-K total scores. Amongst the 150 participants, 76 and 94 belonged to the low- and high-QoL groups, respectively. The mean age of study participants was 50.6 ± 13.1 and 56.2 ± 12.3 in the low- and high-QoL group, respectively (P = 0.005). There were no significant differences in sex, relationship with the patient, education level or religious affiliation, according to the FC QoL. However, the proportion of married individuals was higher in the high-QoL group (84.8%) than that in the low-QoL group (P = 0.019). The resilience score was also higher in the high-QoL group than in the low-QoL group (62.3 ± 17.1 vs. 54.0 ± 16.4; P = 0.002). Moreover, the high-QoL group tended to spend less time on caregiving than the low-QoL group. The high-QoL group showed higher social support and family function scores. Regarding preparedness for death, the interquartile ranges of preparedness scores were 2–4 and 3–4 for emotional and practical preparedness, respectively. Compared with the low-QoL group, the high-QoL group showed higher scores in both emotional (P = 0.001) and practical preparedness (P < 0.001).

Table 1: Characteristics by FCs’ QoL level.

Range FC’s QoL Highd (n=94) P-value IQR Lowd (n=76) Caregiver’s factors Age 44–62 50.6±13.1 56.2±12.3 0.005 Female sex 61 (80.3) 68 (72.3) 0.230 Spouse 32 (42.1) 37 (39.4) 0.717 Education more than college 38 (50.0) 56 (60.2) 0.184 Married 53 (69.7) 78 (84.8) 0.019 Professing a religion 38 (50.7) 52 (55.9) 0.498 Resiliencea 47–69 0–100 54.0±16.4 62.3±17.1 0.002 Caregiving environment Hours of caregiving per day 12–24 0–24 20.2±6.6 17.5±8.2 0.023 Days of caregiving per week 5–7 0–7 6.0±1.7 5.3±2.1 0.027 Months of caregiving 1–9 10.1±14.6 6.6±9.7 0.066 Level of social supportb 61–91 0–100 72.0±19.9 78.0±15.6 0.034 Family function levelc 5–8 0–10 5.6±2.7 6.8±2.4 0.006 Preparing for death Emotionally 2–4 1–5 2.9±1.0 3.4±0.9 0.001 Practically 3–4 1–5 2.7±1.0 3.6±0.7 <0.001 Factors associated with high QoLTable 2 presents the results of the univariate and multivariate logistic analyses for high QoL. In univariate analysis, older FC (odds ratio [OR], 1.04 per 1-year increase; 95% CI, 1.01– 1.06), fewer caregiving days (OR, 0.83 per 1-day increase; 95% CI, 0.70–0.98), hours (OR, 0.95 per 1-h increase; 95% CI, 0.91–0.99) and being married (OR, 2.42; 95% CI, 1.14– 5.13) were associated with high QoL. Besides, higher levels of family function (OR, 1.18; 95% CI, 1.04–1.34), social support (OR, 1.02; 95% CI, 1.00–1.04) and resilience (OR, 1.03; 95% CI, 1.01–1.05) were also associated with high QoL. Regarding preparedness for death, both emotional and practical preparedness were significantly associated with high QoL (OR, 1.72 for emotional and 3.86 for practical). Stepwise multivariate analysis identified factors associated with high QoL, including high practical preparedness (OR, 3.66; 95% CI, 2.14–6.25).

Table 2: Factors associated with high FC QoL.

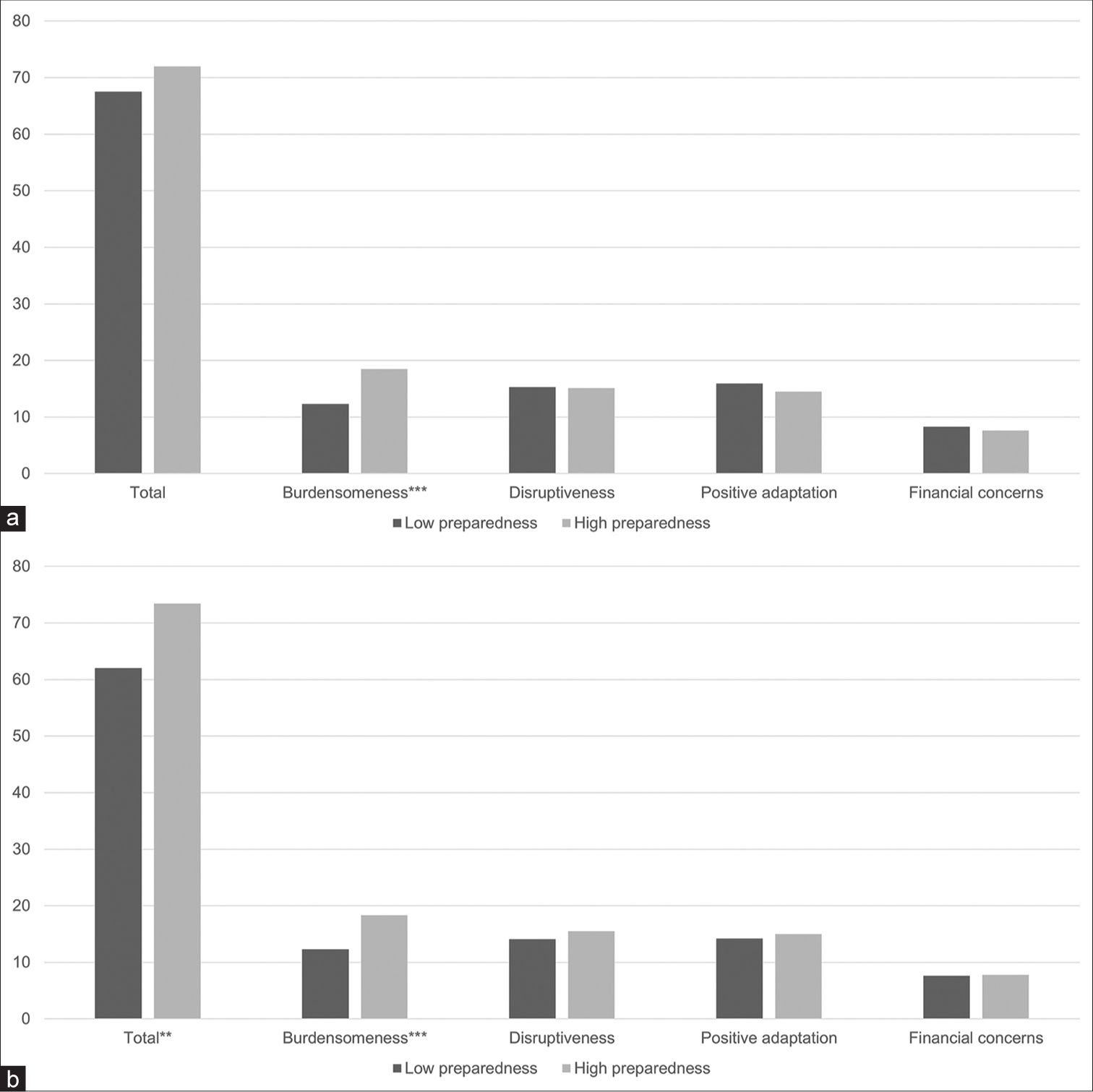

Univariate P-values Stepwise multivariate P-values OR (95% CI) Adjusted OR (95% CI) FC’s age (per 1-year increase) 1.04 (1.01–1.06) 0.006 1.04 (1.00–1.07) 0.042 Female FC 0.64 (0.31–1.33) 0.232 Non-spouse 1.12 (0.61–2.07) 0.717 Caregiving days (per 1-d increase) 0.83 (0.70–0.98) 0.030 Caregiving hours (per 1-h increase) 0.95 (0.91–0.99) 0.025 0.92 (0.87–0.98) 0.006 Caregiving months (per 1-m increase) 0.98 (0.95–1.00) 0.076 0.97 (0.93–1.00) 0.043 High educational level of FC (college graduate or more) 1.51 (0.82–2.79) 0.184 Married FC 2.42 (1.14–5.13) 0.021 No religion of FC 0.81 (0.44–1.49) 0.498 Functional family function (per 1-point APGAR increase) 1.18 (1.04–1.34) 0.007 Social support level (per 1-point increase) 1.02 (1.00–1.04) 0.036 High resilience (1-point increase) 1.03 (1.01–1.05) 0.003 Well prepared (per 1-point increase) Emotionally 1.72 (1.23–2.40) 0.002 Practically 3.86 (2.43–6.12) <0.001 3.66 (2.14–6.25) <0.001 FC’s QoL by preparedness levelFigure 1 presents the estimated total CQOLC-K scores and each subdomain according to the preparedness level. The preparedness level was categorised as low or high based on the median preparedness score. There were no significant differences in the CQOLC-K scores according to emotional preparedness level, except for the burdensome subdomain (12.3 vs. 18.5; P < 0.001). However, the CQOLC-K scores were significantly higher in the high practical preparedness group than in the low practical preparedness group in the total (62.0 vs. 73.4; P = 0.001) and burdensome subdomain (12.3 vs. 18.3; P < 0.001), but no differences were observed in the scores for the other three subdomains.

Export to PPT

Subgroup analysis for the association between practical preparedness and FC’s QoLTable 3 shows the regression coefficient (ß) for total QoL scores per 1-point increase in practical preparedness in total and subgroups. Overall, practical preparedness was significantly associated with FC’s QoL (ß, 5.75; 95% CI, 1.86–9.65). Subgroup analyses found several variables that differentiated the significance (i.e., P ≥ 0.05 vs. P < 0.01). The significant association between practical preparedness and FC’s QoL remained robust in groups with low educational levels, low resilience, low social support and dysfunctional families.

Table 3: Subgroup analysisa for the association between practical preparedness and FC’s QoL.

ßb 95% CI P-value Overall 5.75 1.86–9.65 0.004 Attained education level High school graduate or less 9.02 3.34–14.71 0.002 College graduate or more 4.93 −0.73–10.59 0.087 Resilience level Low (score≤59) 9.05 3.81–14.29 0.001 High (score>59) 3.06 −2.96–9.08 0.313 Social support Low (score<75) 9.23 3.47–15.00 0.002 High (score≥75) 3.78 −1.95–9.50 0.192 Family functionality Functional (score≥7) 3.32 −2.97–9.61 0.294 Dysfunctional (score<7) 10.18 4.65–15.71 <0.001 DISCUSSIONIn this study, practically well-prepared FCs showed higher QoL than poorly prepared FCs, which remained significant in groups with poor psychosocial states. Previous studies have reported several contributing factors associated with FC QoL;[16,20,21] however, studies on preparedness as a factor in FC QoL are relatively rare. A few previous studies have investigated the association between preparedness and FC’s QoL,[22,23] but they were conducted in Taiwan with different measures for preparedness than ours. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the association between preparedness level and QoL in the FCs of patients with terminal cancer in South Korea. We comprehensively evaluated caregiver and caregiving attributes associated with FC’s QoL, such as religion, family function, social support and resilience and ultimately investigated emotional and practical preparedness as aspects of FC’s QoL.

Preparing for a family member’s death is considered an important component of end-of-life care, not only for family members but also for patients and healthcare providers. Amongst the 26 attributes rated as important at the end of life, four items related to a patient’s death were identified.[24] Regular and transparent communication among patients, family members and healthcare providers enables families to better prepare for death.[25] However, despite the fact that communication with health-care providers about death and dying is one of the most crucial aspects of end-of-life care,[26] the lack of discussion of the patient’s approaching death frequently frustrates family members.[27] In particular, truth-telling has been uncommon in East Asian countries, including Korea, because of traditional Confucianism, which emphasises social ethics rather than spiritual issues and regards death as a taboo. Even unawareness of death has been considered a good death in Korea.[28] The association between preparedness and FC’s QoL observed in our study implies that end-of-life discussions, which contribute to FC’s preparedness for death, can improve FC’s QoL.

The level of preparedness observed in our study was relatively low compared with that in previous studies. In an American study using the same method as ours,[10] the mean scores of emotional and practical preparedness were 3.42 ± 1.5 and 3.67 ± 1.5, respectively. These scores are comparable to those of our high-QoL group (3.4 ± 0.9 for emotional preparedness and 3.6 ± 0.7 for practical preparedness). Since preparedness is linked to cultural beliefs and pre-loss caregiver attributes such as depression, anxiety or financial status,[10] cultural differences and unmeasured caregiver attributes may affect the differences in preparedness levels. In addition, according to a cross-cultural study conducted amongst palliative care physicians in East Asian countries,[29] 59% of Korean FCs are reluctant to engage in end-of-life discussions with physicians. We believe that the reluctance to engage in end-of-life conversations originating from death as a taboo is one of the most plausible reasons for low preparedness in Korea.

In our study, the FC’s overall QoL was significantly related to practical preparedness, not to emotional preparedness, which was consistent with a previous finding.[23] Practical adaptation to the loss could be as vital as an emotional one, according to the ‘dual process model’ proposed by Stroebe and Schut.[30] During the pre-loss phase as well, to some FCs, practical uncertainty could be more distressing than the psychosocial aspects.[31] In addition, significant differences were observed only in the burdensome domain, but the explanation for these remains unclear. Further studies are needed to elucidate the mechanisms by which different QoL domains are associated with preparedness.

Our subgroup analyses revealed that the association between practical preparedness and QoL was prominent in FCs with lower education, low resilience, low social support and dysfunctional families. This suggests that the relative contribution of practical preparedness to QoL is greater in the psychosocially poor group. These results increase the robustness of understanding of the intricacy of the process of preparing for death and the importance of preparedness assessment according to FC’s attributes and caregiving environment.

Caregiver preparedness for death can be assessed using a multidimensional approach. Carr suggested that preparedness can be approached as emotional and practical dimensions,[11] which we used to assess preparedness for death in this study. Previous studies have assessed emotional and practical preparedness with each single question, ‘How prepared do you think you are for the death of the patient emotionally (or practically)’?[10] Other research groups have suggested the multidimensional nature of preparedness as medical, psychosocial, spiritual and practical dimensions[32] or as cognitive, affective and behavioural aspects.[31] In a recent study,[33] researchers suggested a preliminary framework for FC preparedness based on establishing both present and future certainties. However, a consensus regarding the best preparedness assessment has not been reached.[33]

In the current study, besides practical preparedness for death, other factors associated with FCs’ QoL were identified (i.e., FC’s age and objective care burden), which were consistent with previous results.[34] Increased daily time spent on caregiving was a significant predictor of QoL,[35] and caregiving duration also showed a significant impact on the QoL and supportive care needs.[36] Caregivers who devote the majority of their time to the patient may struggle to find time for themselves, making it challenging to manage other obligations, including financial burden, which negatively affects their overall QoL.[35] Therefore, it is important for family members to share and divide caregiving time, and further, supporting programmes or services are needed to lessen the time spent on patient care.

This study had several limitations. First, we could not establish a causal relationship between preparedness level and QoL because of the cross-sectional study design. In addition, preparedness can change and vary at different caregiving points.[31] Longitudinal and interventional studies are required to confirm the relationship between preparedness and QoL. Second, since preparedness can be affected by various factors such as caregivers’ emotional symptoms, daily living competencies or financial status,[10] these unmeasured covariates might have influenced the results. Third, the results observed in this study cannot be generalised to other populations because it was conducted with Korean FCs of patients with terminal cancer in inpatient palliative care units. Finally, the validity of the Korean version of death preparedness was not formally tested. To address this, we conducted a brief translating process: Two bilingual doctors first translated the questionnaire and reached a consensus and then a pilot test was performed with 13 samples (i.e., doctor, nurse, social worker, patient and caregiver), who provided feedback.

CONCLUSIONAmongst Korean FCs of patients with terminal cancer, QoL was significantly linked to practical preparedness for death, not to emotional preparedness. Our findings warrant the personalised assessment to evaluate each FC’s needs and preparedness levels. Moreover, to enhance FCs’ QoL during the end of life, specific palliative care services to help FCs prepare the death practically are needed through developing programmes and intervention studies.

Comments (0)