Chronic inflammation is a significant factor in breast cancer (BC) development and prognosis.[1] BC is the most prevalent cancer among women, accounting for a quarter of all cancer cases and leading in mortality rates.[2-4] In the cancer microenvironment, up-regulation of proinflammatory cytokines has a significant role in the progression and angiogenesis of the tumour by stimulating the stromal cells and modifying the cell cytology, accelerating the tumour growth and metastasis, while anti-inflammatory cytokines inhibit cancer cell proliferation and impede inflammation.[5,6] Elevated proinflammatory markers were found in the inactive lifestyle[7] and are associated with increased and persistent fatigue in BC survivors.[8]

Yoga, an ancient therapy of Indians, is known for maintaining physical, mental and spiritual sanity.[9] In recent years, yoga has been embraced to promote their well-being and as a supportive therapy during the conventional treatment of an illness. Yoga encompasses a spectrum of asanas (poses) that range from simple to complex poses and are inherently reflective.[10] In BC, yoga as a supportive therapy was a practical intervention, alleviating physical symptoms and psychophysiological distress and enhancing the quality of life.[11,12]

Tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukins (ILs)-6, and IL-1-beta (IL-1β) are proinflammatory markers and are potential risk markers of BC.[13] TNF-α activates nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-κB), which, in turn, releases genes-related inflammation,[14] contributing to tumorigenesis and metastasis of BC by degradation of the cell matrix, angiogenesis and invasion.[15] In animal models, elevated TNF-α showed poor prognosis and shorter lifespan[16] and is correlated with oxidative stress causing inflammation in the brain.[17] TNF-α is significantly upregulated in BC and showed a positive correlation of their role as prognostic biomarkers.[18] Higher levels of TNF-α are linked to the advancement of BC.[19]

IL-1β is released by the activated macrophages; exposure to IL-1β causes regional inflammation reaction while high levels cause extensive inflammation, coupled with tissue injury and invasion of the tumour.[20] IL-1β and vascular endothelial factor (VEGF) are pivotal in the initiation and maintenance of angiogenesis; IL-1β led to the maturation of endothelial precursor cells, tumour cell migration and formation of metastatic deposits. IL-1β, on binding to its receptor IL-1 receptor type 1, initiates downstream signalling, activating genes dependent on NF-Kb promoting cancer growth.[21] Its aggressiveness in the breast tumour is linked as a potential marker in the prediction of bone metastasis in BC.[22]

IL-6, a pro-inflammatory cytokine released by the lung epithelial cells, is crucial for tumour growth; it influences the synthesis of oestrogen in BC, regulating through cell receptors and participating in tumour progression through angiogenesis.[9] IL-6 directly communicates with tumour cells, initiating crucial intracellular signal pathways that promote cell migration and decrease apoptosis.[23] In mice, lower levels of IL-6 showed a notable effect on VEGF, causing a reduction in intra-tumour angiogenesis.[24]

Few studies carried out on the effect of yoga on inflammatory markers were reported among BC survivors who completed BC treatment except endocrine therapy. Tumour necrosis factor receptor II (TNF-RII) was significant (P = 0.03) at 12 weeks of Iyengar yoga but was not significant for IL-6 (P = 0.87).[25] Post 3 months of Hatha yoga, TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-1β have significantly reduced (P < 0.05) in BC survivors.[26] A study on the effect of therapeutic yoga and meditation for 04 months among the cancer survivors where the majority (65%) of the study population were BC showed significant reduction in IL-1β (P < 0.05).[27] A significant reduction of TNF-α (P < 0.05) was reported 4 weeks post-surgery in the integrated yoga group among BC who had undergone surgery.[28]

The fact chronic inflammation is deeply connected to the development and prognosis of BC, with proinflammatory cytokines playing pivotal roles in tumour progression, angiogenesis and metastasis. Investigating this area could yield valuable insights into the mechanisms by which yoga exerts its effects. Understanding how yoga influences the cancer microenvironment and inflammatory pathways may lead to more effective, integrative treatment strategies that enhance patient’s clinical outcomes. Therefore, it is crucial to prioritise research exploring the intersection of yoga, chronic inflammation in BC. This study aims to elucidate the role of yoga intervention in modulating the proinflammatory markers in newly diagnosed BC patients undergoing neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by surgery.

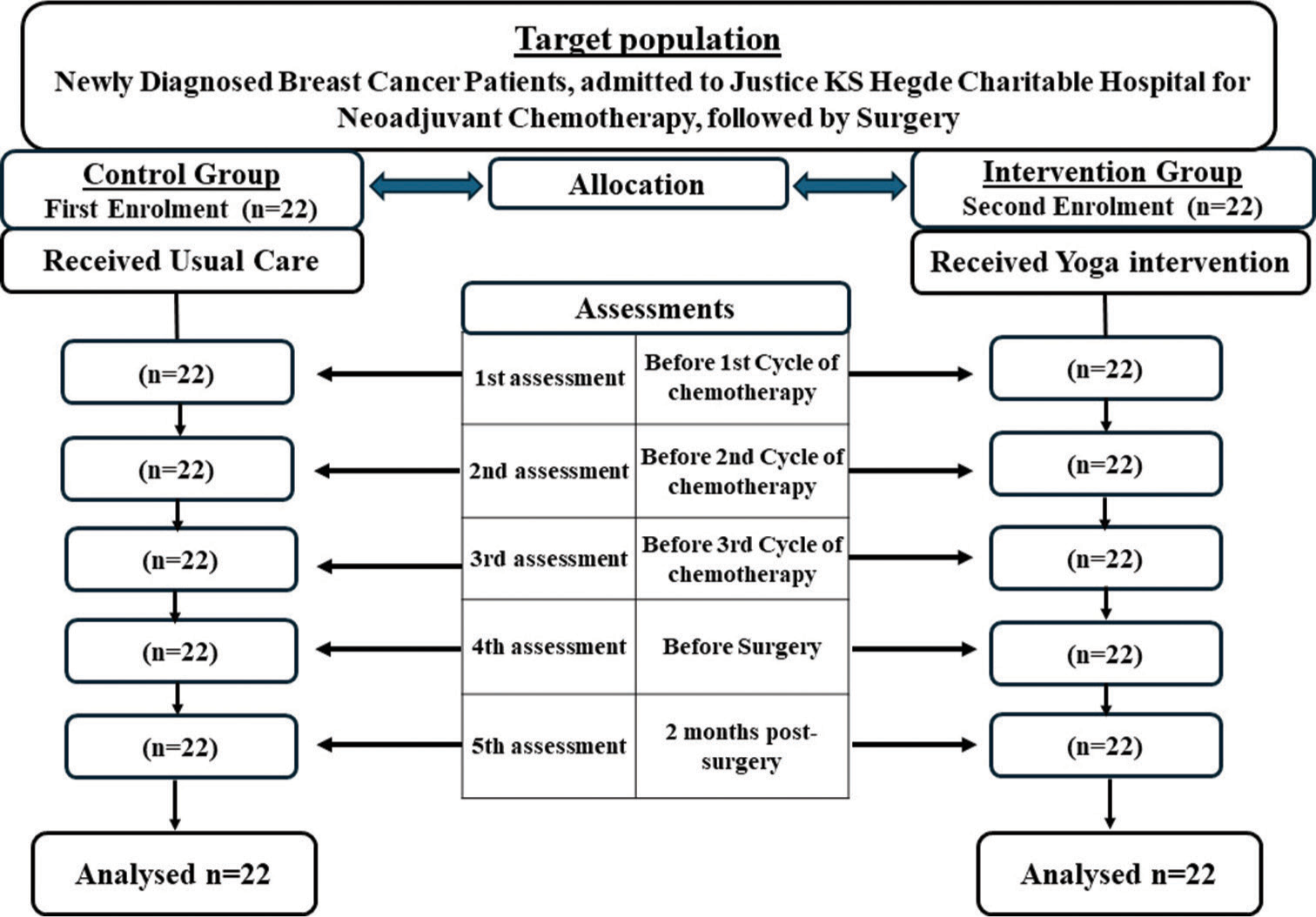

MATERIALS AND METHODS Study design and populationA prospective non-randomised control trial design with a purposive sampling technique was employed for this study. Forty-four newly diagnosed BC with stage II, III and IV without distant metastasis and other associated inflammatory conditions, and those who did not practice yoga in the control group, aged between 30 and 70 years, with the treatment plan regiment of neo-adjuvant chemotherapy, followed by surgery were recruited from Justice KS Hegde Charitable Hospital. The exclusion criteria were those not willing to participate in the study, debilitated patients, inflammatory disease conditions, those not able to perform yoga, any prior treatment of cancer and day-care BC patients. The control participants were recruited prospectively between August 2020 and March 2021; only after completing the data collection of the control group the yoga intervention participants were recruited between April 2022 and July 2023 [Figure 1].

Export to PPT

Data collectionAn information sheet was handed to the participants, and written consent was obtained from each participant who agreed to participate in the study. The confidentiality of the study participants was maintained by securely storing all data, anonymising personal identifiers and ensuring no unauthorised personnel had access to the information collected. The first 22 BC patients meeting the study criteria were assigned to the control group and the following 22 to the yoga intervention group. Data were obtained at 5 time points: Before the first, second and third cycles of chemotherapy, the day before the surgery, and 2 months post-surgery. The data collection time for each patient varied between 20 weeks and 21 weeks. Demographic details were obtained from the case file and interview. Blood samples were obtained using strict aseptic techniques. The separated serum was stored at −80°C in K S Hegde Medical Academy, Central research laboratory – enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) kit from Elabscience, (TNF-α – Catalogue No. E-EL-H0109; IL-1β – Catalogue No. E-EL-H0149; IL-6 – Catalogue No.: E-EL-H6156), ELISA microplate reader, (Tecan Spark) at 450 nm, was used to determine the level of inflammatory markers.

Yoga interventionYoga was administered by a yoga shikshaka (yoga teacher) for 40-minute duration. The intervention consists of pranayama (alternate nostril breathing), Bhramari pranayama (deep inhalation and exhaling slowly while humming), hatha yoga asanas (Pranam mudra, Tadaasana, Hasthautanasana, Padahasasana, Ashwa sanchalanasana, Parvatasana, Shashankasana, Astangasana, Bhujangasana, Virabadra asana, Ardhachakra asana and Trikona asana Virabradra asana) coordinating with the breath, (three sets) and Shavasana (corpse pose), which was administered for 3 consecutive days to ensure that the techniques were mastered properly before the administration of first cycle chemotherapy. There was a weekly telephonic follow-up, and a diary was handed over to maintain their daily practices to ensure compliance during the interval until the next admission to the hospital. Yoga intervention was reinforced under supervision at subsequent admission to the hospital. The supervised reinforced sessions of yoga were continued until the day of surgery and resumed on the 5th and 6th day of post-surgery. Patients performed yoga in the morning between 7 am and 8 am or between 5 pm and 6 pm. The study participants were encouraged to continue performing yoga at home 6 days a week after hospital discharge.

Data analysisData were analysed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences 20. Fisher’s exact test and Chi-square test were employed for homogeneity between groups; Frequency and percentage described the demographic variables. A general linear model repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) assessed the outcomes within the group. Independent t-test compared the outcome between the yoga intervention and the control group.

RESULTSThe mean ages of the study subjects were 51.36 ± 8.61 and 50.64 ± 9.21 years in the yoga intervention and control groups, respectively. The average monthly family income was Rs 19,000 ± 6761.23 in the yoga group and Rs 18,636.36 ± 7877.31 in the control group. Homemakers comprise 27.27% in the yoga group and 36.36% in the control group, with the least 9.09% employed in the yoga group and 4.54% in the control group. The majority were married, 38.63% in the yoga group and 36.36% in the control group. In both the groups, 09.09% each had completed higher secondary. The rest had completed their primary and secondary education. Distribution of the stages of BC is as follows: stage II (22.72% in each group), stage III (18.18% in the yoga group and 15.90% in the control group) and stage IV (9.09% in the yoga group and 11.36% in the control group) [Table 1]. Fisher’s exact test and Chi-square test confirmed homogeneity between groups (P > 0.05).

Table 1: Frequency and percentage distribution of demographic characteristics of newly diagnosed breast cancer patients in the yoga intervention and the control group (n=22+22=44).

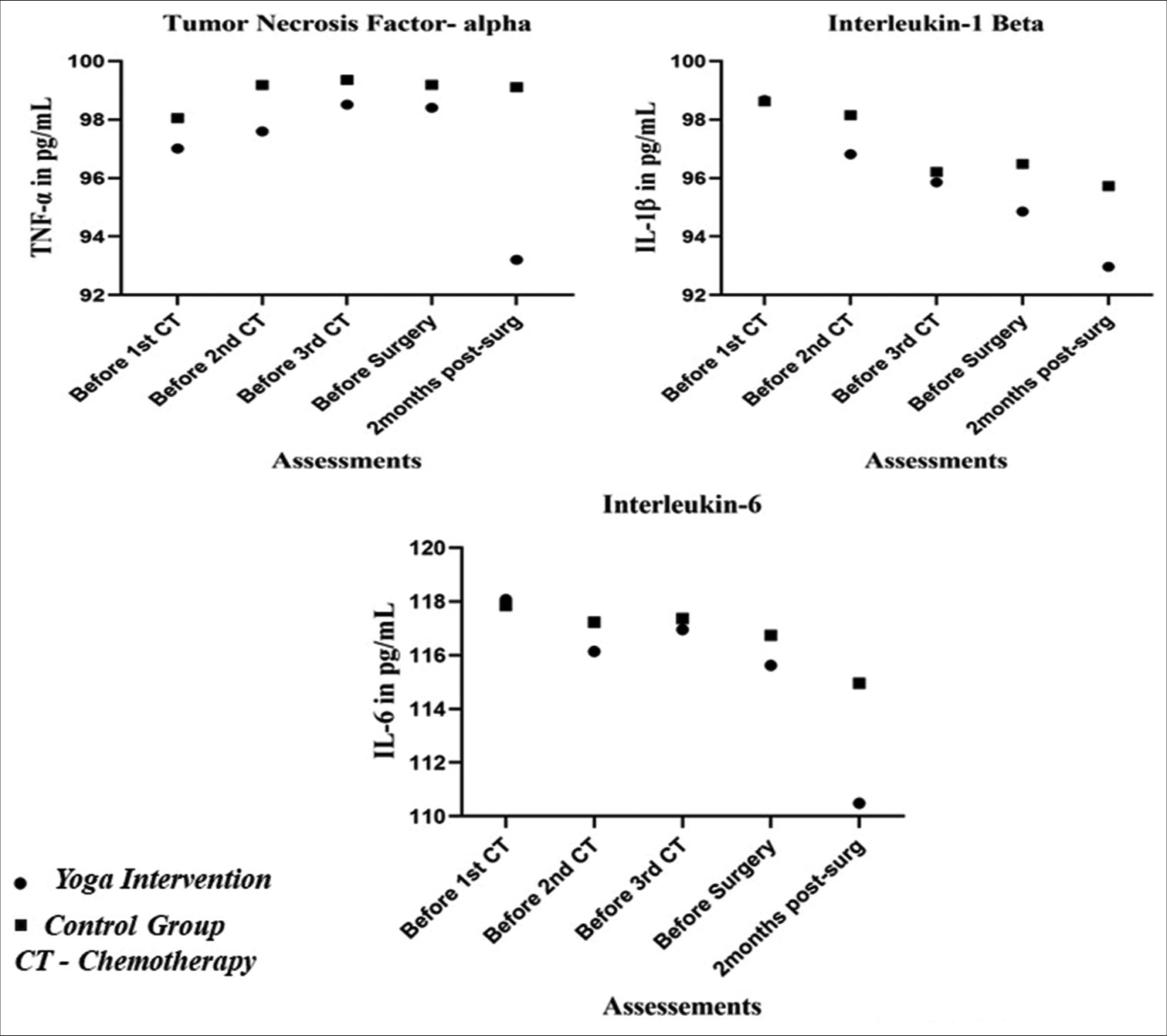

Demographic variables Yoga (n=22) Control (n=22) P f % f % Age in years 31–40 4 9.09 4 9.09 0.921a 41–50 5 11.36 8 18.18 51–60 10 22.72 8 18.18 Above 61 3 6.81 2 4.54 Family income/month <10000 5 11.36 6 13.63 0.991b 10001–20000 8 18.18 8 18.18 >20000 9 20.45 8 18.18 Occupation Homemaker 11 27.27 16 36.36 0.374a Agriculturist 7 15.9 4 9.09 Employed 4 9.09 2 4.54 Marital status Married 17 38.63 16 36.36 1.000b Widow 5 11.36 6 13.63 Education Primary 9 20.45 10 22.72 0.921a Secondary 9 20.45 8 18.18 Higher Secondary 4 9.09 4 9.09 Stage of BC II 10 22.72 10 22.72 1.000a II 8 18.18 7 15.9 IV 4 9.09 5 11.36 Inflammatory markersIn an ANOVA with Greenhouse-Geisser correction, sphericity not assumed, showed statistically significant within-subjects of the yoga intervention group, while no significance was found in the control group. The result depicted were as follows: Serum TNF-α in yoga intervention group (F [4] = 7.11, P = 0.007), control group (F [4] = 0.36, P = 0.674), serum IL-1β, yoga intervention (F [2] = 5.421, P = 0.013), control group (F [2] =1.814, P = 0.177) and serum IL-6 yoga intervention group (F [2] = 5.581, P = 0.004), control group, F (3) =6.13, P = 0.595 [Table 2]. However, the independent t-test comparing the effect of yoga intervention with the control group showed no statistically significant difference (P > 0.05). The mean values showed a consistent downregulation of proinflammatory markers over time in the yoga intervention group. TNF-α at 2 months post-surgery showed that the mean value was 93.21 ± 43.31 pg/mL, which is lower than all previous assessments, whereas, in control, it was upregulated to 99.10 ± 38.81 pg/mL, which is higher than before the 1st chemotherapy 98.04 ± 37.56 pg/mL. A reduction in serum IL-1β and IL-6 was observed in both groups; however, a significant attenuation at 2 months post-surgery in the yoga intervention group is noted compared to the control group. This highlights the beneficial impact of yoga intervention on clinical outcomes by modulating proinflammatory markers in the cancer microenvironment of BC patients. The comparison of the inflammatory marker’s attenuation between groups is projected in Figure 2.

Table 2: Comparison of the within-subject effect of proinflammatory status in yoga intervention and control groups (n=22+22=44).

Proinflammatory markers assessments Yoga intervention Control group Mean±SD F P Mean±SD F P TNF-α Before 1st CT 97.00±9.79 7.11 0.007* 98.04±37.55 0.36 0.674 Before 2nd CT 97.59±0.62 99.17±38.70 Before 3rd CT 98.51±0.67 99.35±38.67 Before Surgery 98.40±1.01 99.18±39.26 2 months post-surgery 93.21±4.93 99.10±38.80 IL-1β Before 1st CT 98.67±2.22 5.42 0.013* 98.61±43.58 1.81 0.177 Before 2nd CT 96.82±3.99 98.14±42.24 Before 3rd CT 95.85±5.56 96.20±41.86 Before Surgery 94.86±5.13 96.47±41.87 2 months post-surgery 92.97±5.10 95.73±42.74 IL-6 Before 1st CT 118.06±1.75 5.58 0.004* 117.84±23.10 6.13 0.595 Before 2nd CT 116.14±2.16 117.22±24.82 Before 3rd CT 116.94±2.22 117.35±25.53 Before Surgery 115.61±1.74 116.73±23.87 2 months post-surgery 110.48±0.69 114.94±24.52

Export to PPT

DISCUSSIONWhile the evidence on yoga intervention in BC survivors is encouraging, there is limited information on yoga intervention’s effects on inflammatory homoeostasis in patients undergoing BC treatment. In the present study, though no statistical significance between the yoga intervention and the control groups (P > 0.05) was found, a significant reduction of the inflammatory markers within subjects of the yoga intervention was observed (P < 0.05), and the mean values across various time points suggested that yoga intervention downregulated proinflammatory markers (TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6) in BC patients undergoing conventional treatment of BC. Kaje et al. and Estevoa, in their systematic review, reported a favourable effect of yoga on markers of inflammation in BC survivors.[9,29]

A randomised controlled trial by Kiecolt-Glaser et al. reported significant decreases in TNF-α, immediately to post-12 weeks of hatha yoga intervention and at 3 months follow-up (P < 0.05) in BC survivors,[26] Long Parma et al., on the effect of 6 months of yoga-based exercise in BC survivors, showed a decreased level of TNF-α when compared to comprehensive exercise and exercise of choice, the mean post-score minus pre-score and standard deviation were 184.61 (750.28), 860.74 (1620.38), −212.13 (756.10), respectively.[30] Bower et al. reported that Iyengar yoga in BC survivors was found to maintain the stability of soluble TNF-RII when compared to the health education group.[25] A study by Rao et al. on the effects of yoga on post-operative outcomes and wound healing in BC patients found that serum TNF-α was downregulated in the integrated yoga group, whereas in the control group, it was upregulated, though statistically, it was not significant.[31] These study results corroborated our research finding where TNF-α was attenuated in the yoga intervention group, and in the control group, it was up-regulated. These findings provided evidence of the impact of yoga on modulating the TNF-α and improving the clinical outcomes of BC patients. Consistent with the findings of our study result where IL-1β within the yoga intervention group was significantly downregulated (P = 0.013), Patel et al., in their pre-experimental study, found a significant decrease of plasma IL-1β (P = 0.003) post-therapeutic yoga intervention among cancer survivors where BC constitute 65%.[27] In our study between the yoga intervention and the control groups, it was not significant; however, Kiecolt-Glaser et al. reported a significant difference between the hath yoga and waitlist in BC survivors in IL-1β immediately to intervention (P = 0.037) and during follow-up at 3 months (P = 0.01).[26] The contrasting findings between the groups warrant further studies to be explored for the therapeutic effect of yoga in reducing IL-1β levels in BC patients, despite the significant differences within the yoga group in our study.

A randomised controlled trial by Kiecolt-Glaser et al. reported significant decreases in IL-6 immediately and at 3 months follow-ups (P = 0.05) of Hatha yoga among BC survivors,[26] However, Parma et al. in their three-arm randomised control yoga exercise, comprehensive exercise and exercise of choice found no significant difference between the groups (P > 0.05).[30] In our current study, a significant decrease in IL-6 was observed within subjects of yoga intervention but no statistical difference between the groups was noted. Further, investigation with larger samples on the yoga intervention effect in modulating the IL-6 in BC patients may shed more light.

Limitation and strengthThis study faced several limitations. It was not a randomised controlled trial and was conducted at a single institution, employing a prospective non-randomised control trial. The counselling and the regular visits by social workers during the hospital stay and the social support received by the patients in the control group could have a placebo effect, which was not under the control of the researcher. In addition, the study participants were not blinded. Despite these limitations, the study has a striking strength. Notably, there were no dropouts among the participants, and the sample population was homogeneous, all receiving the same conventional BC treatment regimen. To prevent sample contamination, the control group was recruited first, followed by the yoga intervention group. To the best of our knowledge, this study is pioneering in its integration of conventional BC treatment with yoga intervention from the very beginning of the cancer treatment process.

CONCLUSIONYoga helped downregulate proinflammatory markers (TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6) in BC patients undergoing conventional treatment; this indicates incorporation of yoga as a complementary therapy alongside conventional BC treatment has the potential to modulate inflammation and improve clinical outcomes of BC patients.

Comments (0)