Females undergo profound anatomical and physiological changes during pregnancy and puerperium. These changes are adapted by the female body to sustain foetal development during pregnancy and subsequent delivery at term1. However, this increased metabolic load may unmask underlying diseases and co-morbidities and make the mother’s body vulnerable to complications2. Frequent requirement of invasive interventions also exposes these mothers to surgical and anaesthetic complications2-4. Obstetric patients are, therefore, at greater risk of potentially fatal complications than normal adult population2,3. Consequently, many obstetric patients require invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV), inotropic support (IS), and blood transfusions among other interventions, which require admission to intensive care units (ICUs)2-4. With advances in the management of many chronic diseases, more high-risk patients with co-morbidities are conceiving and surviving pregnancies. This is further expected to increase the number of obstetric patients in ICUs5,6.

In recent times, globally enhanced quality and availability of healthcare has improved maternal-foetal outcomes4-6. However, there is still a tremendous disparity in the human and material resources available worldwide for such needs3-6. This disparity is seen even among different areas of the developed countries3-6. High maternal and foetal morbidity and mortality persist in certain parts of the world3. Reducing maternal mortality rate is therefore an important goal of the ‘The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development’ envisioned by the United Nations in 20157.

In recent times, severe acute maternal morbidity (SAMM) and maternal near-miss have gained recognition as measures of quality of obstetric health care4. These include critically ill patients who narrowly escape death due to obstetric or non-obstetric complications but do not contribute to the maternal mortality ratio. However, these patients may be left with severe morbidities requiring admission to ICUs and, at times, prolonged health infrastructure support2-6.

The available data on obstetric patients requiring ICU admission are scarce and heterogeneous8-23. Among the published studies, the difference in the quality of centres, studied populations, characteristics of the admitted patients, and clinical outcomes is remarkable8-23. The causes of ICU admissions in obstetric patients, however, remain uniform across the globe, with hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (HDP) and its complications, obstetric haemorrhage (OH), and sepsis forming the bulk8-23. The maternal ICU mortality rates vary significantly from less than two per cent in developed countires21-23 to almost 50 per cent in certain centres14,16 in developing country settings. Considering this paucity and heterogeneity of information, and a requirement for a continuous update on these data, we conducted a retrospective study of the demography, clinical characteristics, and outcomes of obstetric patients who needed admission to ICU at our centre.

Materials & MethodsThe study was done at the department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology (OBG), Government Lalla Ded Hospital, a teaching tertiary-care maternity hospital, Government Medical College, Srinagar, Jammu and Kashmir, India. The centre, dedicated to the patients of OBG, is located in the picturesque Kashmir Valley in the Northern Himalayan region of South Asia. In addition to the Kashmir Valley, the hospital also receives referrals from the adjoining Chenab Valley and the Pir Panjal region of the Jammu division as well as the Union territory of Ladakh. This region has a population of approximately 10 million and consists of both urban centres as well as rural areas that include places deep within the Himalayas with difficult mountainous terrain. This study was a retrospective cohort study initiated after obtaining Institutional approval from the Institutional Review Board, Government Medical College, Srinagar, Jammu, and Kashmir, from March 2022 to February 2023.

On average, the hospital attends to approximately 500 patients of OBG per day in the outpatient department (OPD). The OBG admissions vary between 80 to 150 patients daily. The in-patient department (IPD) has a capacity of 750 beds with occupancy of at least 80 per cent throughout the year. The hospital has 24-h emergency service, including operation theatres, a blood bank, and an ICU with four beds dedicated to the patients of OBG. The ICU is level 324, semi-open, and attended by the department of Anaesthesia and Critical Care (ACC) and the department of OBG. Specialists from other medical and surgical departments are available on call round the clock whenever needed. The centre also has a high-dependence unit with 12 beds used as an intermediate level of care between IPD and ICU. Patients are admitted to ICU only after a collective decision by intensivists and OBG specialists. In case patients require specific procedures or care not available at the centre, intensive care ambulances are used to transport the patients to other centres of the Government Medical College, Srinagar, located in the same city within a distance of 5 km. The hospital also has an in-house neonatal ICU.

Study sampleThe records of all obstetric patients admitted to our centre’s ICU from March 2022 to February 2023 were retrieved using the hospital record system including ICU registers, ICU charts, IPD registers, operation theatre records and the individual case files of the patients. All the patients admitted to the ICU during pregnancy or within 42 days of delivery were included in the study. A senior OBG specialist recorded the data with the help of a resident doctor. At least 90 per cent of the data was cross-checked by another Critical Care specialist.

Variables studiedThe data compiled included demographic characteristics, co-morbidities, diagnosis at admission, and type of surgery (in case of post-operative patients) done before admission to the ICU. Interventions in the ICU, like endo-tracheal intubation, IMV, non-invasive ventilation (NIV), inotropic support, and blood transfusion were also recorded. The outcome data comprised of the duration of stay in ICU in hours, referral to other centres for non-OBG or multi-specialty care, death, discharge from the hospital, or shift to a lower level of care like HDU or IPD. In addition, the total number of OPD patients seen, patients admitted to IPD, patients admitted to ICU, surgeries done and vaginal deliveries (VD) conducted by the hospital during the study period was also retrieved.

Statistical analysisThe categorical variables were recorded as numbers and percentages of the total were estimated. The continuous variables were summarised as mean±standard deviation (SD). Multivariate cox regression analysis was used to determine the association of variables with the mortality risk. For the significance of this model likelihood ratio test was used. R software version 4.4.0 was used to fit the cox regression proportional model using survival package25.

ResultsDuring the study period, our centre attended to 1,59,839 patients in OPD and admitted 32,665 patients to the IPD. Of the admitted patients, 22,745 (69.63%) belonged to rural areas, and 9920 (30.36%) belonged to urban centres. A total of 20,676 deliveries were conducted during the study period, out of which 14,100 (68.19%) had caesarean sections (CS) and 6576 (31.8%) had VD (Table I). A total of 583 patients were admitted to the ICU during the given time frame (Table I). Out of these, 525 (90.05%) were obstetric patients and the rest were gynaecology patients. A majority (76%) of the obstetric patients admitted to the ICU belonged to rural areas (Table I). Only three (0.57%) patients were unmarried (Table I).

Table I. Demography and co-morbidities of obstetric patients seen at the hospital (March 2022 to February 2023)

Variable studied n (%) Number of patients seen in OPD 159839 Number of patients admitted in IPD (P) 32665 Patients admitted residing in rural areas 22745 (69.63%) Patients admitted residing in urban areas 9920 (30.36%) Total deliveries conducted (Q) 20676 Deliveries by caesarean section 14,100 (68.19%) Deliveries by vaginal delivery 6,576 (31.81%) Total patients admitted to ICU (R) 583 Total gynaecology patients admitted to ICU 58 (9.94) Total obstetric patients admitted to ICU (N) 525 (90.05) Age (mean±standard deviation) 30.07 ± 4.58 Age (yr; min–max) 18 – 43 10-29 243 (46.29) 30-39 274 (52.19) 40-49 8 (1.52) Married 522 (99.42) Rural 399 (76) Urban 126 (24) Hypertension 189 (35.23) Anaemia 172 (32.76) Diabetes 65 (12.38) Heart disease 49 (9.33) Epilepsy 25 (4.76) Kidney disease 19 (3.61) Lung disease 24 (4.57) Liver disease 35 (6.66)Hypertension, including both essential hypertension and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (HDP; including pre-eclampsia, eclampsia, and pregnancy-induced hypertension), was the most common co-morbidity seen in 35.23 per cent of patients, followed by anaemia (32.76%) and diabetes (12.38%; Table II).

Table II. Diagnosis of obstetric patients at the time for admission to intensive care unit

Variable studied n (%) Total number of patients admitted to intensive care unit (N) 525Diagnosis in patients admitted for obstetric reasons- total (percent of N)

(one patient can have more than one condition)

499 (95.04) Hypertensive disorder of pregnancy and complications 159 (30.28) Post-partum haemorrhage 130 (24.76) Placenta praevia 79 (15.04) Eclampsia 65 (12.38) Intra-uterine foetal death 50 (9.52) Abortion 46 (8.76) Abruption 43 (8.19) Twin delivery 37 (7.04) Ectopic pregnancy 33 (6.61) Post-operative/obstetric sepsis 23 (4.38) Uterine rupture 4 (0.76) Diagnosis in patients admitted for non-obstetric reasons - number (percent of N) 26 (4.95 %) Anaphylaxis 2 (0.38) Pulmonary complications 7 (1.33) Community-acquired pneumonia 3 (0.57) Hospital-acquired pneumonia 1 (0.19) Status asthmaticus 2 (0.38) Interstitial lung disease 1 (0.19) Cardiac causes 8 (1.52) Valvular heart disease 3 (0.57) Arrhythmia 2 (0.38) Cardiomyopathy 3 (0.57) Diabetic keto-acidosis 3 (0.57) Acute kidney failure 2 (0.38) Portal hypertension with gastric bleed 1 (0.19) Status epileptics 1 (0.19) Anaesthesia related complications 2 (0.38)Most (95.04%) patients were admitted to the ICU due to obstetric causes (Table II). HDP (30.28%) along with post-partum haemorrhage (PPH; 24.76%) were the two most common conditions seen in obstetric patients needing admission to ICU. Other causes of obstetric haemorrhage (OH), like placenta praevia (15.04%), abruption (8.19%), and uterine rupture (0.76%), were also recorded (Table II). Other critical clinical conditions in these patients were intra-uterine foetal death (IUFD; 9.52%), twin pregnancy (7.04%), and post-operative sepsis (4.38%; Table II). Patients admitted for eclampsia were 12.38 per cent of these patients (Table II).

Non-obstetric medical and surgical causes were responsible for only 4.95 per cent of the admissions to the ICU. These included patients who presented with anaphylaxis (0.38%), pulmonary (1.33%), cardiac (1.52%), renal (0.38%), neurological (0.19%), hepatic (0.19%), and diabetic (0.57%) complications (Table II).

Most obstetric patients (84.38%) were admitted to ICU after surgery (Table III). Of these 357 (80.58%) were emergency and 86 (19.41%) were elective surgeries. CS was the most common (66.59%) surgery done in these patients. Of the 14,100 CS done at the hospital, only 2.09 per cent of patients needed ICU admission (Tables I and III). These formed 56.19 per cent of all obstetric ICU admissions. Hysterectomy done at the time of caesarean section comprised 11.28 per cent of the surgical obstetric cases needing ICU admission (Tables I and III). Of the 6576 vaginal deliveries conducted at our hospital during this period, only 66 (approximately 1%) were admitted to ICU. These formed 12.57 per cent of the total obstetric patients admitted to ICU (Tables I and III). Laparotomy for ectopic pregnancy (EP; 6.77%) was another common surgery done in these patients before ICU admission (Table III).

Table III. Type of surgery/procedure done in obstetric patients prior to admission to intensive care unit

Variable studied n (%) Total number of patients admitted to intensive care unit (N) 525 Vaginal delivery 66 (12.57) Total surgeries 443 (84.38) Elective 86 (19.41) Emergency 357 (80.58) Caesarean section 295 (66.59) Caesarean hysterectomy 50 (11.28) Laparotomy for ectopic pregnancy 30 (6.77) Exploratory laparotomy 27 (6.10) Dilatation and curettage 23 (5.19) Manual removal of placenta 14 (3.16) Caesarean myomectomy 1 (0.22) Laparoscopy for ectopic pregnancy 3 (0.67)In the ICU 22.28 per cent of patients needed invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV), whereas only six per cent were managed by NIV. Inotropic support (IS) was required in 98 (18.66%) patients. Blood transfusion was needed in 50 per cent of the patients. Most patients (87.23%) were successfully discharged or shifted to a lower level of care like ward or HDU. Only 35 (6.66%) of the obstetric patients in ICU needed transfer to another centre for non-OBG or multi-specialty care which was not possible at our centre (Table IV).

Table IV. Care received and outcomes in obstetric patients admitted to the intensive care unit

Variable studied n (%) Total number of patients admitted (N) 525 Invasive mechanical ventilation 117 (22.28) Non-invasive ventilation 32 (6.09) Oxygen supplementation 219 (41.71) Inotropic support 98 (18.66) Blood (component) transfusion 263 (50.09) ICU duration in h (range: Min - Max) 4 - 336 ICU duration in h; mean (standard deviation) 33.02 (70.99) Death* 32 (6.53) Transfer out (for non-obstetric/multi-specialty care) 35 (6.66) Downgraded care (shifted to ward/discharged) 458 (87.23)A total of 32 obstetric patients died in our ICU during the study period. After excluding the patients transferred out, the net ICU mortality rate for obstetric patients admitted to our ICU was 6.53 per cent (Table IV). We did not have the mortality data of the patients transferred out of our centre.

Both antepartum and post-partum obstetric haemorrhage, was the main obstetric condition in patients who died after admission to ICU. Most of the patients died after emergency surgeries, the most common of which was the caesarean section done with (12.48%) or without hysterectomy (31.25%). Six patients (18.72%) died after exploratory laparotomy out of which 2 had ruptured ectopic pregnancy. Six patients (18.72%) died due to sepsis. Intrauterine death occurred in 1/3rd of the patients before death (Table V).

Table V. Obstetric and non-obstetric conditions in obstetric patients who died after admission to ICU

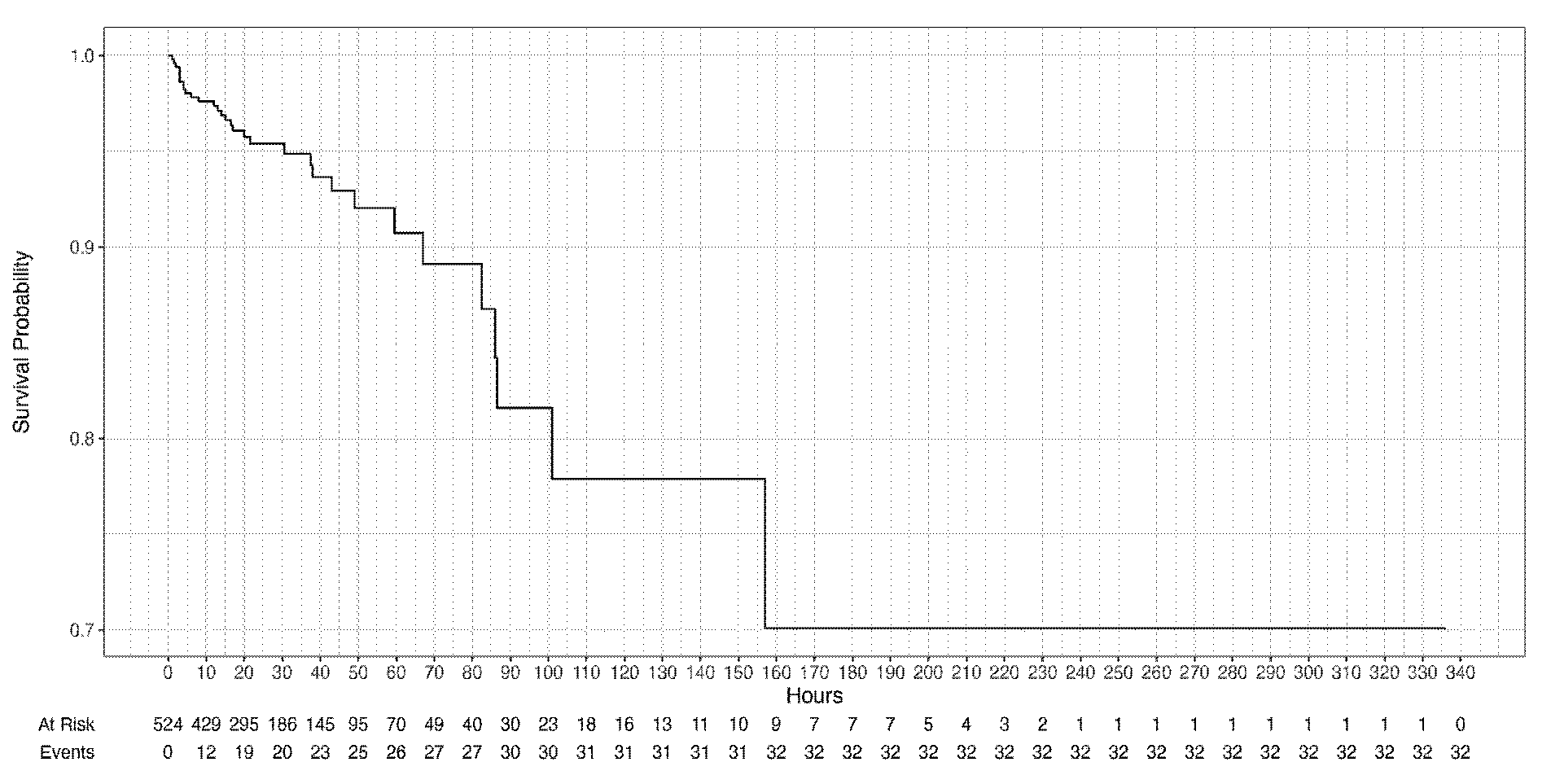

Total no. of deaths (n) = 32 Obstetric/non-obstetric diagnosis n (%) Obstetric causes/conditions Intra-uterine death 10 (31.2) Twin pregnancy 1 (3.12) Eclampsia 5 (15.6) Abruption 3 (9.36) Placenta praevia 2 (6.24) Post-partum haemorrhage 9 (28.08) Ruptured ectopic pregnancy 2 (6.24) Non-obstetric causes/comorbidities Hypertension 13 (40.56) Anaemia 12 (37.44) Heart disease 4 (12.48) Lung disease 3 (9.36) Diabetes 2 (6.24) Liver diseases 2 (6.24) Kidney disease 1 (3.12) Sepsis 6 (18.72) Surgeries done in patients prior to death Total number of post-operative patients who died 21 (65.52) Emergency surgery 20 (62.5) Elective surgery 1 (3.12) LSCS 10 (31.25) Caeserean hysterectomy 4 (12.48) Examination under anaesthesia and proceed 1 (3.12) Exploratory laparotomy 4 (12.48) Laparotomy for ectopic pregnancy 2 (6.24)Multivariate cox regression analysis of mortality revealed statistically significant (P<0.05) increased risk of death in patients with heart disease (Hazard ratio [HR)=8.26, 95 per cent Confidence Interval (CI)=0.01-67.17, P<0.05), who required IMV (HR=35.5, CI= 3.14-401.75, P<0.05) or IS (HR=12.06, CI=1.96-74.19, P<0.05) and those admitted after IUFD (HR=5.17, CI=1-26.75, P<0.05) or admitted after undergoing laparotomy for EP (HR=50.2, CI=1.43-1766.87, P<0.05). The analysis also revealed a decreased risk of death for those admitted after VD (HR=0.1, CI=0.01-0.73, P<0.05; Table VI). Time survival plot shows that more than 3/4th of maternal mortalities happened within first 72 h of admission (Figure).

Table VI. Multivariate Cox regression analysis chart of variables affecting mortality of obstetric patients admitted to intensive care unit

Hazard ratio P value 95% confidence Interval Maternal age 0.96 0.065 0.89-1.03 Rural residence vs urban residence 2.02 0.49 0.7-0.79 Intra-uterine foetal death* 5.17 0.049 1-26.75 Twin pregnancy 4.2 0.351 0.2-86.29 Anaemia 1.28 0.820 0.22-6.59 Diabetes 4.4 0.206 0.44-43.84 Hypertension 1.06 0.942 0.23-4.73 Eclampsia 0.38 0.229 0.07-1.83 Abruption 0.39 0.287 0.03-2.62 Placenta praevia 1.23 0.897 0.05-29.34 Heart disease* 8.26 0.048 0.01-67.17 Kidney disease 0.93 0.967 0.02-39.56 Lung disease 0.28 0.196 0.04-1.92 Liver disease 0.19 0.228 0.01-2.85 Post partum haemorrhage 4.28 0.203 0.45-40.22 Sepsis 1.21 0.842 0.18-8.18 Surgery 8.52 0.139 0.49-145.79 Vaginal delivery* 0.1 0.022 0.01-0.73 Hysterotomy 0.17 0.21 0.01-2.68 Caesarian section 1.5 0.651 0.25-8.7 Caesarian hysterectomy 1.09 0.961 0.03-30.95 Examination under anaesthesia and proceed 4.05 0.488 0.07-211.99 Exploratory laparotomy 0.97 0.981 0.06-14.98 Laparotomy for ectopic pregnancy* 50.2 0.031 1.43-1766.87 Invasive mechanical ventilation* 35.5 0.003 3.14-401.75 Supplemental oxygen support 0.27 0.076 0.06-1.15 Inotropic support* 12.06 0.007 1.96-74.19 Blood transfusion 2.07 0.375 0.41-10.37

Export to PPT

DiscussionIdeally, obstetric patients should be managed in a multi-specialty centre with obstetric, neonatal and other non-obstetric facilities26,27. However, this may not always be possible, even in developed world21-24,26,27. OBG departments may work as stand-alone units or maternity hospitals like our centre. However, the lack of non-obstetric specialities at these centres may make patient care challenging21-24,26,27.

Most of the studies conducted on obstetric patients admitted to ICU are single-centre8-20 retrospective studies8-14,20. Only a few are prospective15-19, multi-center20, population based21-23 or with a case-control design13,14. Increased severity of illness on admission to ICU, as well as mortality, has been seen in un-booked obstetric patients as well as patients who did not receive antenatal care10,17. Patients with HDP (including pre-eclampsia, pregnancy-associated hypertension, and eclampsia) and its complications, along with other causes of OH, formed the bulk of our patients. These causes are similar in all regions of the world and have remained largely unchanged over time8-23. Multiple pregnancies (7% of our cohort) have also been seen to be associated with a higher risk for ICU admission12.

Like previous studies in developing countries, hypertension (including both essential hypertension and HDP), anaemia, and diabetes were the most common co-morbidities in our patients8-23,28,29. Anaemia is the most common nutritional disorder in pregnant females globally and is associated with poor maternal and foetal outcomes, including a higher risk of ICU admissions29. Management of patients with a high prevalence of anaemia and haemorrhage consequently requires a robust blood transfusion facility; more than half of our ICU patients required such services.

VD has been seen to have a lower risk of general anaesthesia, wound infection, maternal near miss, and placenta praevia and placenta accreta in subsequent pregnancies30-32. In our study, VD decreased mortality in patients admitted to ICU.

Although emergency CS has been shown to increase the risk for ICU admissions13,16,30, this demarcation between emergency and elective surgeries may not always be clear in obstetric care. The occurrence of hysterectomy at the time of CS (11% in our cohort) has been reported to increase the risk of ICU admissions16.

Unlike the developed world, where ruptured EP is an important cause of maternal mortality, EP does not form a major proportion of maternal mortality in India due to a higher number of other preventable causes like HDP, PPH, anaemia, and sepsis33-35. The incidence of EP is expected to increase globally due to an increase in CS deliveries and assisted reproductive technologies33. Patients with EP needing surgery after rupture and haemo-peritoneum have higher mortality35. Our study showed an increased risk of ICU mortality in these patients. This finding, though unique to our study, is not surprising given the delayed diagnosis, late presentations, and referrals of such patients at our centre. Since EP is a great mimicker, a high degree of suspicion and early intervention may save lives as well as future fertility in such patients33-35.

IUFD is associated with acute maternal complications, like clinical chorioamnionitis, PPH, and retained placenta36-38 as well as an increased risk of diabetes mellitus, renal disease, cardiovascular, and cerebrovascular diseases in the long term36. Although India contributes the highest number of stillbirths in the world, the data on these patients are inadequate37. Patients admitted after IUFD to the ICU had a statistically significant risk of death in our ICU.

The proportion of non-obstetric medical causes of maternal mortality and maternal near-miss, like heart diseases, has increased in recent times, especially in developed countries8-23,39,40. In our study, patients with heart diseases had a statistically significant increased risk of death when admitted to ICU.

The requirement of IMV and IS was seen in patients with high severity scores and haemodynamic instability. This is reflected in the higher mortality risk of these patients in previous studies14 as well as ours. The bulk of maternal mortality in our cohort occurred in the initial 72 h of the ICU admission. Therefore, timely transfers, prompt referrals, and early guided clinical decisions are essential in these patients. Our study also favours the technical feasibility of managing critically ill obstetric patients in stand-alone maternity centres like ours given very low transfer rates of our patients.

Our study had several strengths. First, our centre with high patient turnover manages booked as well as un-booked patients. This reflects in the large number of patients enrolled in the study in only one year period. Second, very low transfer-out rate at our centre leaves less scope for follow up losses. The patients admitted to our ICU in this study are, therefore, more representative of our centre as well as the general population of the area.

Our study also had some limitations. First, it was a single-centre study. Second, we analysed data from only one year. The protocols for admission to ICU may vary from centre to centre as well as from time to time, even in the same centre. Third, our centre caters to a very heterogeneous area with both urban as well as far-off rural areas. A significant variation in the clinical profile of these patients is therefore expected. We did not do this segregation in our ultimate analysis. Finally, ours is a dedicated centre for patients of OBG. This may lead to a referral bias to our centre with an under-representation of non-OBG medical or surgical causes of ICU admission in our cohort.

Overall, the data on the demography, clinical characteristics, and mortality in obstetric patients admitted to ICU is scarce and heterogeneous. However, the causes of ICU admission in these patients are uniform across the globe and have not changed over time. HDP and OH continue to be the most important causes of ICU admission in these patients. Mortality in obstetric ICU patients remains low. However, those admitted with heart diseases and who require IMV or IS are at increased risk of death in ICU. Similarly, those admitted after IUFD or after laparotomy for EP, are also at increased risk of mortality. On the other hand, patients admitted after VD, have a statistically significant reduced risk of mortality in ICU. ICUs at maternity hospitals can be run with satisfactory outcomes by in-house obstetricians, intensivists, anaesthetists, and neonatologists with the support of other specialties whenever needed.

Comments (0)